Weaponized “Development”: How Xinjiang Aid Drives Repression

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched “Xinjiang Aid” (对口援疆) in 1997 as a poverty-alleviation and ethnic-unity program in the Uyghur Region. In practice, it is a comprehensive system of repression, coercion, and assimilation. Xinjiang Aid has become a driving force in the displacement and dispersion of Uyghur and other Turkic peoples by integrating cadre deployments, industrial expansion, labor transfers, and political indoctrination.

Official statistics indicate that authorities subjected millions to state-imposed labor through the transfer of “surplus rural laborers” (农村富余劳动力) to production facilities between 2014 and 2023. Xinjiang Aid is one of the central programs facilitating such transfers under coercive conditions both within the region and into mainland China. Provincial governments, corporate entities, and local cadres collaborate to carry out the Xinjiang Aid strategy through paired assistance programs (对口支援), mandatory quotas for local authorities, state subsidies, and surveillance through supervision. These mechanisms simultaneously move industries into the Uyghur Region and disperse Uyghur and other Turkic peoples into tightly controlled, heavily surveilled, and isolating environments far from their families and communities.

In this report, Uyghur Rights Monitor traces the policy evolution of Xinjiang Aid: from its early rollout in the wake of the Ghulja Massacre, to the institutionalization of the pairing assistance system after the Urumchi Massacre, to the acceleration of coerced labor transfers amidst genocide in the Uyghur Region, to the subsequent rebranding to “employment assistance” in response to international scrutiny. The report examines the scale of labor transfers Xinjiang Aid carried out and analyzes its governance structure. It demonstrates that Xinjiang Aid is not a benign development project but a central mechanism of repression, embedding Uyghur forced labor into production lines in China and supply chains worldwide.

Background and Framework

The CCP Central Committee (CCPCC) and the State Council formally launched Xinjiang Aid in 1997 in the wake of violent crackdowns following the Ghulja Massacre in February 1997. From the outset, Beijing framed it as a long-term “pairing assistance” mechanism in which wealthier eastern provinces would provide funds, cadres, and expertise to support underdeveloped prefectures in the Uyghur Region.

The initiative drew on earlier experiments of cadre transfers dating back to the 1970s. By the 1990s, the Chinese government had already sent more than 800,000 cadres from its inner provinces to work in the Uyghur Region. By the launch of Xinjiang Aid, these practices had already become a key governance tool for embedding CCP authority in the region.

At the March 1996 National Conference on Xinjiang Stability Work (新疆稳定工作会议), chaired by former general secretary Jiang Zemin, the CCP explicitly tied cadre deployment to ethnic policy and “frontier security.” The Conference selected more than 200 veteran cadres from seven provinces (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shandong, Henan) and national ministries to work in seven prefectures and 17 institutions in the Uyghur Region. The following year, Beijing institutionalized these practices into the Xinjiang Aid Cadre Plan (对口援疆干部计划), which would become a cornerstone of the program.

From its inception, Xinjiang Aid was never simply a development assistance scheme. It fused local governance with Beijing’s agenda for coercive social engineering—first through cadre deployments to entrench CCP authority, and later through mass labor transfers and political indoctrination. It evolved into a platform through which cadres, companies, and provincial governments carried dual mandates: to deliver economic leverage to the central government while enforcing assimilation of the Uyghur Region.

Policy Evolution of Xinjiang Aid

“Blood Transfusion” (输血) to Condolidate Control

Chinese officials framed the earliest phase of Xinjiang Aid as a “blood transfusion” (输血) program. During this phase, China’s eastern provinces sent cadres, experts, and investment into the Uyghur Region to stabilize unrest following the 1997 Ghulja Massacre.

Cadre transfers to the Uyghur Region became systematic during this period. Between 1997 and 2013, Beijing dispatched seven batches totaling more than 7,000 cadres from 19 of its inner provinces to the Uyghur Region. An eighth batch of more than 4,000 followed in 2014, and the number of cadre transfers has increased since. Provincial and municipal governments expanded their own Xinjiang Aid programs in parallel.

Pilot projects tested the system by embedding cadres as Party secretaries for Xinjiang Aid in municipal leadership, providing political oversight at the local level. The pilot included Qumul City and Qorgas County in 2002 and added Aqsu City, Yengisheher County, and Hotan City in 2005.

Cadre transfers included officials and technical staff. Party and government officials, typically on three-year deployments, were embedded in local administrations to enforce central directives on stability, ethnic policy, and ideological work. Their responsibilities included supervising security campaigns, overseeing propaganda and education initiatives, managing quota systems for labor transfers, and ensuring that local officials complied with Beijing’s objectives.

Professional and technical staff, including managers, technicians, and teachers, were deployed to schools, factories, hospitals, and state enterprises for 18-month terms. Beyond technical support, their work included promoting Mandarin, reorienting local curricula towards CCP ideology, and assimilating Uyghurs and other Turkic groups into state-planned socioeconomic schemes.

This initial phase emphasized political consolidation, not yet on large-scale labor transfers. By embedding officials from mainland China into county and municipal leadership in the Uyghur Region, Xinjiang Aid created the bureaucratic and institutional channels through which coercive labor transfers and large-scale assimilation policies would later operate.

“Comprehensive Assistance” (综合援疆) through Pairing Assistance

The 2009 killing of Uyghur workers at a factory in Shaoguan, Guangdong, exposed the vulnerability of Uyghur workers in China’s industrial hubs and increased ethnic tensions. When Uyghur protestors gathered in the streets of Urumchi that July to demand justice, the Chinese government responded with one of the most violent crackdowns in recent Uyghur history. The Urumchi massacre marked a critical turning point.

Beijing convened the First Xinjiang Work Forum in May 2010 and the Second forum in Urumchi a week later. These forums reframed Xinjiang Aid as a nationwide responsibility and institutionalized the pairing assistance system (对口支援), formally linking 19 Chinese provinces and municipalities with 12 prefectures, 82 counties, and 12 Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) divisions in the Uyghur Region. This was expanded in 2014 to 13 prefectures, 86 counties, and 14 XPCC divisions.

In 2010, the CCP convened the First Xinjiang Work Forum in Beijing. In the same year, Beijing formalized a nationwide “pairing assistance” (对口援疆) architecture, designating 19 eastern and central provinces/municipalities to support 12 prefecture-level areas, 82 counties/cities, and 12 XPCC divisions in the region. In 2014, the Second Xinjiang Work Forum took place in Beijing. The same year, the CCP expanded the pairing assistance program to include Karamay City and the XPCC’s 11th and 12th Divisions, raising coverage to 13 prefectures, 86 counties/districts, and 14 XPCC divisions.

This “comprehensive assistance” phase extended Xinjiang Aid’s scope from cadre deployments and infrastructure investments to include labor pipelines that would move Uyghur and other Turkic individuals away from their communities and across the region and mainland China. State media messaged these transfers as “poverty alleviation” and “ethnic mingling” (民族交融) efforts. In reality, the programs expanded surveillance, coercion, and assimilation, creating the infrastructure for mass forced labor.

“Blood Production” (造血) and Mass Arbitrary Detention

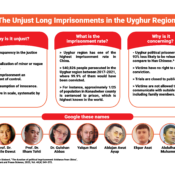

Under the 2014 Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism (严打暴恐活动专项行动), Xinjiang Aid shifted to “blood production” (造血), which emphasized economic exploitation and population dispersion through coerced labor transfers. This phase coincided with the mass arbitrary detention of over one million Uyghurs and other Turkic people in camps and other repressive policies that constitute genocide.

Provinces such as Guangdong, Shandong, and Anhui established industrial parks, vocational centers, and factories in the Uyghur Region, often next to detention facilities, while transferring tens of thousands of workers to inner provinces, sometimes directly from camps. County governments enforced relocation quotas with subsidies and indoctrination campaigns.

“Vocational training centers” became pipelines into factories, merging political indoctrination with labor exploitation. International observers, an independent tribunal, nine legislative bodies across the globe, and major international NGOs, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have recognized these abuses as crimes against humanity and genocide. A 2022 United Nations report likewise concluded that those violations “may amount to international crimes, in particular, crimes against humanity.”

The CCP does not tolerate refusal to participate in state-imposed labor schemes. Individuals who resist government directives risk being sent to camps, prosecuted under counter-terrorism or extremism provisions, stripped of household registration, or having their families targeted. Such refusal is often branded as political disloyalty or “extremist” behavior, triggering reprisals ranging from heightened surveillance and loss of social benefits to arbitrary detention in camps or prisons.

“Employment Assistance” (就业帮扶) under International Scrutiny

In 2019, regional officials reported 2.86 million “surplus rural laborer” transfers (person-times). In 2023, officials reported 3.05 million transfers in just the first nine months before they ceased publication of such regional data.

Facing global scrutiny under the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) and United Nations and European Union investigations, the CCP rebranded Xinjiang Aid and similar programs as “employment assistance” (就业帮扶). Yet coercion persists: cadres enforce quotas, dispatch companies recruit and transport workers, and paired provinces continue to expand projects. Transfers have become geographically dispersed to reduce visibility, but surveillance, indoctrination, and restrictions on mobility persist.

Investigations published in 2025 by The New York Times and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism demonstrate that, despite this rebranding, the underlying system of coercion remains very much intact. These reports confirm that paired assistance programs and cadre-enforced quotas funnel Uyghurs into labor pipelines that serve national industrial priorities. Key sectors, including textiles, cotton, seafood, solar, and critical minerals supply chains, remain deeply implicated in Uyghur forced labor, underscoring that coercion is not incidental but systemic, embedded in the very design of China’s “development” programs like Xinjiang Aid.

Central Leadership, Strategic Directives, and Implementation

Xi Jinping has consistently tied development work in the Uyghur Region to national security and assimilation. At the Second Xinjiang Work Symposium in Beijing in 2014, he called for instilling a “correct view of the motherland” and promoting “identification with the great motherland, the Chinese nation, Chinese culture, and the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” In 2017, then regional Party Secretary Chen Quanguo endorsed Xi’s directives, describing “vocational skills education and training transformation centers” (职业技能教育培训中心) as a “good method” to achieve Xi’s policy goals. More recently, Foreign Minister Wang Yi reframed such programs as a human rights initiative at the 2024 Munich Security Conference, asking: “Don’t the Uyghur people have the right to work and the freedom to employment?”

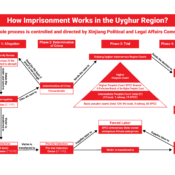

These statements are not isolated rhetoric—they cascade through a vertically integrated system that operationalizes central policy. At the top, the CCP Central Committee sets directives at Xinjiang Work Forums. The State Council’s Xinjiang Work Coordination Group translates these into operational plans, and the National Development and Reform Commission’s (NDRC) Regional Revitalization Department manages day-to-day implementation.

At the provincial level, 19 provinces/municipalities pair with prefectures, counties, and XPCC divisions in the Uyghur Region. These partnerships channel funds, projects, cadres, and quotas into designated localities. Provinces are expected not only to provide financial assistance but also to embed themselves in local governance, driving both economic and ideological objectives.

At the county level, cadres ensure compliance through quota enforcement and household-level pressure. They often work with Human Resources and Social Security bureaus that license labor-dispatch companies to act as intermediaries between state authorities and enterprises. Labor dispatch companies recruit, “train,” and transfer workers on behalf of county administration.

Transfers follow a structured pipeline: cadres pressure households; officials channel workers into “vocational” and “patriotic” training; authorities move large groups via chartered buses or trains; and upon arrival, factory managers and party committees monitor workers under constant surveillance. The process deliberately displaces Uyghur and other Turkic workers from their families and communities, dispersing them into Han-majority environments where assimilation is enforced.

Conclusion

Xinjiang Aid is not a development program in any meaningful sense. It is governance and assimilation by coercion. Quotas on provinces, cadres, and companies ensure transfers regardless of consent. Political indoctrination permeates every stage, transforming factories into sites of surveillance and re-education. By dispersing Uyghur and other Turkic people into China’s inner provinces, the CCP extends assimilation beyond the Uyghur Region, isolating workers from their families and communities while eroding their ethnic and religious identity.

The program’s economic and political objectives are inseparable. “Poverty alleviation” is an exercise in social engineering. Xinjiang Aid recasts Uyghur identity as a security threat to be neutralized through engineered labor dependency and exploitation, displacement, and dispersion.

Xinjiang Aid illustrates how state-led development policy can be weaponized into an instrument of repression and genocide. Far from alleviating poverty, it institutionalizes systemic coercion, embedding Uyghur and Turkic peoples into supply chains under conditions of forced labor. For policymakers, businesses, and human rights monitors, recognizing Xinjiang Aid as a central pillar of repression is essential to breaking complicity, strengthening enforcement of sanctions, and upholding international law against ongoing crimes against humanity in the Uyghur Region.